Io?

Appartengo

alla luce

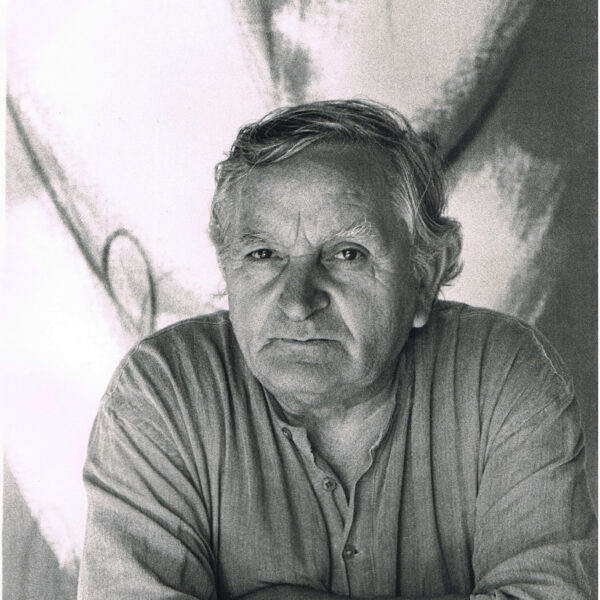

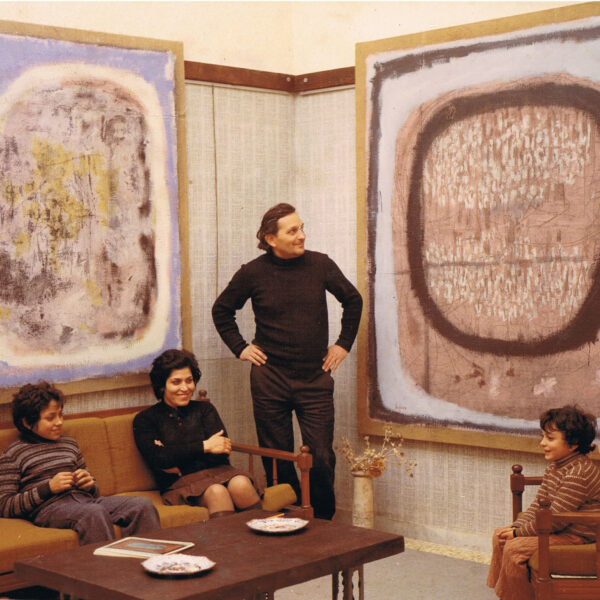

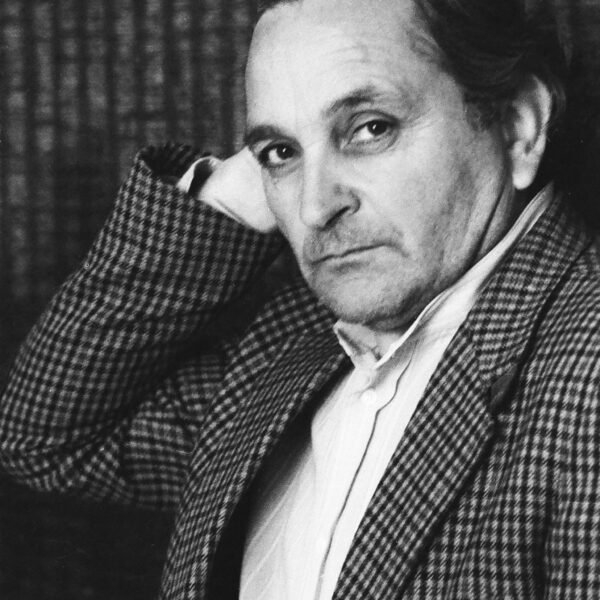

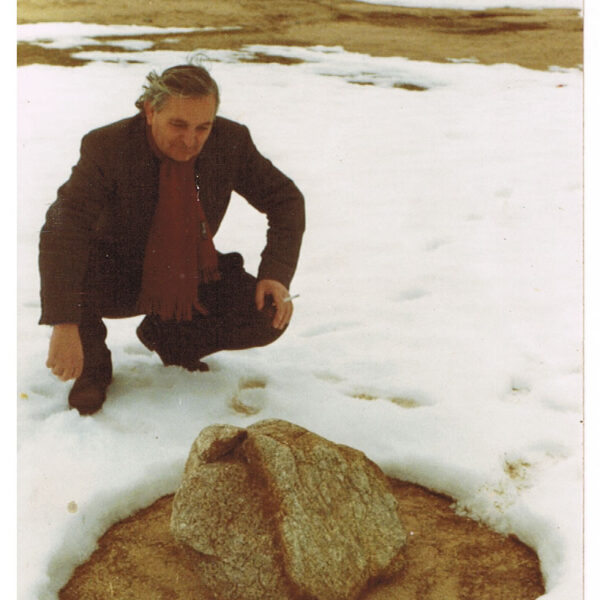

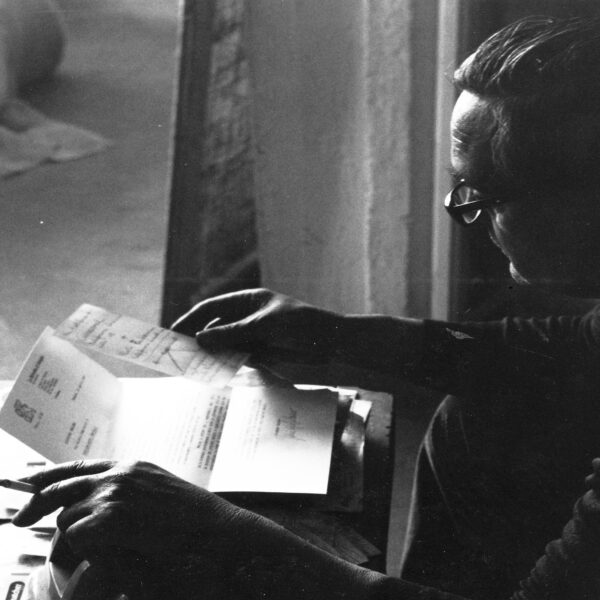

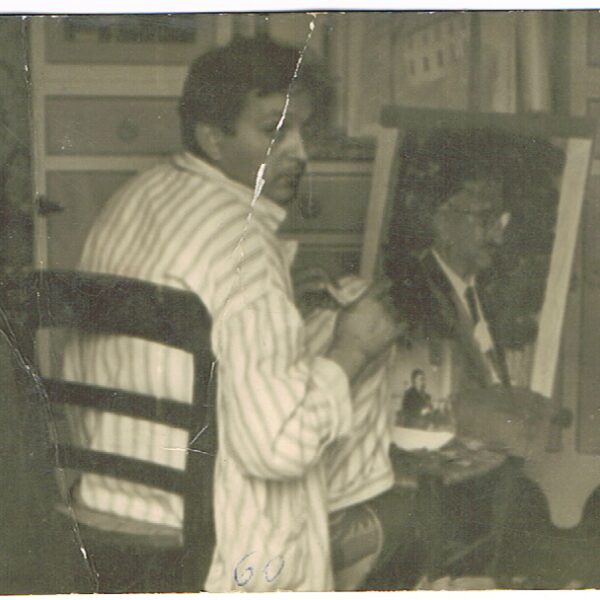

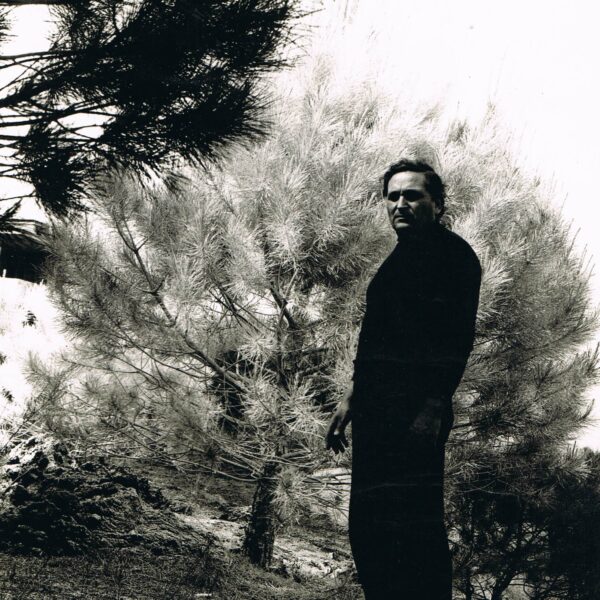

Sono nato il 25 aprile del ‘29. Anzi, per la precisione, sono venuto alla luce. E dal momento che alla luce ci sono venuto, non l’ho potuta più lasciare. Io appartengo alla luce. L’ho cercata dentro i quadri, nella pittura, ma si è trattato di un posto come un altro. La luce la inseguono i pittori come gli amanti: tutti gli altri la inseguono lo stesso, ma in altri modi. Qualcuno la trova addirittura, consumando la carne del suo stesso corpo ma quella cosa lì si chiama santità. Personalmente mi ha interessato la luce quella vera, fisica. Quella cosa chiara che permette di vedere -e noi impariamo a vedere ogni volta che apriamo gli occhi- Quella cosa bella, bellissima, che entra nei quadri e che ne tira fuori il colore. Che si muove, che cambia, ma è sempre solo lei. Che gioca con le ombre e con la materia. Quella cosa che ti fa crescere e che ti emoziona. Nella pittura, come nella vita è questo che importa veramente: l’emozione. L’emozione e la luce. Anzi, l’emozione è la luce. E’ per questo fatto che i miei quadri sono, in fondo, solo un pretesto. Il quadro non deve essere fine a sé stesso. Meglio ancora se non è affatto finito. Il quadro è ipotesi, possibilità. Non è una cosa ferma, non è né un’immagine e né un concetto. E’ movimento. Il quadro è quando lo spazio si mette a fare l’amore col tempo.

E quando si fa all’amore è difficile a restarsene fermi. Ma allora, mi direte, i quadri non ce l’hanno un significato? Certo! Ma la luce è in sé il significato, è un messaggio. E’ verità. E la verità poi, è mobile proprio come la luce. Leonardo cinque secoli fa diceva “Per raggiungere l’essenzialità delle cose bisogna togliere e non aggiungere!”. E noi per gli stessi cinque secoli abbiamo continuato con ‘sta stupidaggine autentica, di aggiungere pittura alla pittura, gesti ai gesti, parole alle parole. Ma che possibilità diamo al quadro se noi lo affoghiamo di forme, di concetti, di immagini, di significati? Dal momento che io do un significato, un nome, una ragione ad una cosa, io questa cosa la condanno alla limitazione. A quella che è la mia stessa limitazione. Vi faccio un esempio: Se io vedo una bella donna, la verità è che quella donna è bella. Basta. Mi emoziona, questa donna, mi manda in Paradiso. Detto questo, che me ne frega a me come si chiama, chi è, chi non è. Se questa donna è figurativa oppure concettuale. Tutte queste considerazioni, quando ho visto una verità piena e rotonda come ’sta emozione di femmina bella, diventano inutili. Io ho già guardato oltre i vestiti, oltre lo stesso suo corpo e ho veduto quella luce che questa donna si porta appresso. E ogni donna, se ne porta sempre appresso una. Che cos’è la trasparenza allora, se non il tentativo di eliminare ogni corpo opaco che si metta in mezzo tra i nostri occhi e la luce? Per secoli lo spazio dietro al quadro è stato uno spazio morto. Era necessario far vivere quello spazio, perché è là che la verità aspetta di essere scoperta, ancora ed ancora. La trasparenza è questo proprio, andare all’altro spazio, quello spazio che raramente nella vita si raggiunge: è la verità quello spazio, è il paradiso, è un muro. Un muro qualsiasi, che, però, grazie alla trasparenza diventa un luogo, abitabile dall’uomo e dalla vita. Quel muro di materia, fatto di mattoni ed intonaco, testimonia per la prima volta, la luce. Come da sempre, il corpo, di carne e sangue, testimonia dell' anima. E non è mica poco. Raggiungere L’Altro Spazio, andare alla Luce, è un problema fondamentale per tutti i pittori, come per gli amanti. Ma la pittura si è sempre fatta su un cosa (il quadro) che ne nascondeva un'altra (il muro). I corpi degli amanti invece, quelli, non si nascondono mai, nemmeno quando si coprono l’un l’altro. I pittori ti dicono: “Ma io ti dipingo lo spazio infinito, che t’importa se ti tolgo un poco di spazio reale”. E che discorso è? E’ Falsità! L’Infinito non ammette negazioni, non ammette falsità. Mark Rothko, uno dei grandissimi, lo aveva capito questo. Già faceva trasparenza, ma la sua era una cosa metafisica. Lui tirava al massimo il colore, te lo faceva sentire, ti faceva avvertire la tela sotto che vibrava, intuivi che c’era una vita dietro. E la luce ti spostava lo sguardo dal centro verso il margine, fuori dal quadro, come per aggirarlo. La luce ti imponeva di muoverti verso la sua fonte, e questa, è una cosa immensa. E più andavi al margine più la cosa si faceva nitida, chiara. Poi, però, ti avvicinavi al quadro, lo andavi a toccare e ti accorgevi che quella luce era finta, era fatta con la pittura. Era bella quella luce là, caspita, ma era una menzogna tremenda. Era un colore che ti dava l’idea di essere una luce, ma non certo la luce che diventava lei stessa, il colore. Un fatto tremendo questo, terribile. Pure a Lucio Fontana, un altro grandissimo, dava fastidio il quadro. Era cosciente, come Rothko, che bisognava andare oltre la superficie della tela, oltre il quadro, verso la luce. Che disse allora, Fontana: “Quadro, io non ti voglio dipingere, io ti taglio”. Una cosa intelligentissima questa, una protesta, che però ancora una volta non risolveva il problema. Il Taglio era un fatto di teatro, era una provocazione lucidissima, radicale, ma non apparteneva interamente alla Pittura. Presupponeva una gestualità, un atto d’inizio: un Via! Ed io, invece, ho dovuto capire che la pittura esiste sempre un poco prima ed un poco oltre dell’atto di dipingere. Detto tutto questo, devo confessare una cosa. Non c’è nessuna intelligenza nella trasparenza. Non c’è metafisica, alcuna difficoltà, ragione o volontà. La trasparenza è solamente un fatto di Necessità.

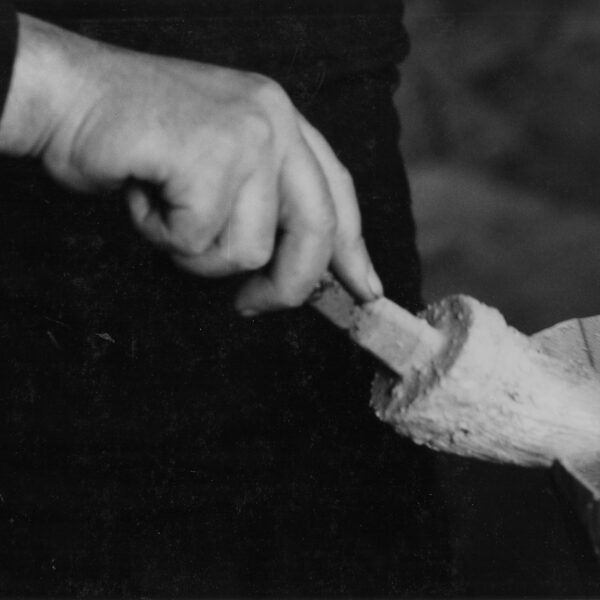

E’ stata una necessità per me tirare un filo dalla tela.

Per necessità da quel varco, la luce è entrata nel quadro.

E la luce è arrivata fino al muro.

E l’ha illuminato, il muro.

Ed alla fine, sempre per la stessa necessità iniziale, la luce è tornata indietro.

Questo è quanto.

Ma quando è tornata indietro sulla tela, nel quadro, Quella lì, la luce, aveva già fatto tutto. Si era portata appresso il colore, la materia, l’emozione, il movimento, la fisica, la metafisica, la matematica, la storia, la geografia. Tutto lo spazio del mondo e tutto il tempo dell’uomo e, con queste cose, tutta la verità di Dio. E’ così che funziona la trasparenza: è così che la luce diventa messaggio all’umanità. E’ questa la strada che ho seguito. Può essere, quindi la trasparenza, davvero una parola nuova per la pittura? Se è vero questo, allora diamoci sotto, diamoci da fare, perché un giorno arriveremo a concepire quadri senza corpo, totalmente trasparenti, fatti solo di luce e di colore, senza tela che li sostenga. Senza menzogna che li giustifichi. Immagina, una parete completamente trasparente, fatta solo di luce e di colore, che viva, che cambi appresso alle emozioni tue. Che ti protegga senza per questo isolarti. Immagina: e sei in paradiso.

Di cos’è fatto il Cielo? Di niente!<br>

Di che colore è il Cielo? Nessuno!<br>

Il Cielo è Vuoto e Trasparente.<br>

Eppure d’Azzurro sostiene le Nuvole.<br>

Me?

I Belong to

the Light

I was born on April 25, 1929—or, to be precise, I came into the light. And from the moment I did, I could never let it go. I belong to the light. I sought it in my paintings, through painting, but that was just one place among many. Painters chase light like lovers; everyone else does too, but in their own ways. Some even find it by consuming the very flesh of their bodies, though that is called sainthood. Personally, I was interested in real light, physical light. That clear thing that allows us to see—and we learn to see every time we open our eyes. That beautiful, radiant thing that enters paintings and pulls color out of them. That moves, that changes, yet remains the same. That plays with shadows and matter. That thing that makes you grow and that moves you deeply. In painting, as in life, that’s what really matters: emotion. Emotion and light. Actually, emotion is light. For this reason, my paintings are, in the end, just a pretext. A painting shouldn’t be an end in itself. Better if it isn’t finished at all. A painting is a hypothesis, a possibility. It isn’t something fixed, nor is it an image or a concept. It’s movement. A painting is when space begins to make love with time.

And when it comes to making love, staying still is nearly impossible. So, you might ask, do paintings have no meaning? Of course, they do! But light itself is meaning—it’s a message. It’s truth. And truth, like light, is always in motion. Five centuries ago, Leonardo said, “To get to the essence of things, you must remove, not add!” And yet, for the same five centuries, we’ve stubbornly insisted on doing the opposite—layering paint upon paint, gestures upon gestures, words upon words. But what chance do we give a painting if we smother it with forms, concepts, images, and meanings?

The moment we assign a meaning, a name, or a reason to something, we limit it—we trap it within the bounds of our own limitations. Let me give you an example. If I see a beautiful woman, the truth is simple: she is beautiful. That’s it. She stirs me, she lifts me to paradise. Beyond that, what do I care about her name, her identity, or whether she’s figurative or conceptual? When confronted with a truth as full and radiant as the beauty of a woman, all those questions fade away. I’ve already looked beyond her clothes, beyond even her body, and I’ve seen the light she carries. Every woman carries a light within her.

So, what is transparency, if not an effort to remove every opaque barrier that stands between our eyes and the light? For centuries, the space behind a painting was a dead space. That space needed to come alive because that’s where truth waits to be discovered, again and again. Transparency is precisely this: reaching for another space—the space where truth resides, where paradise lies, where even a simple wall becomes something extraordinary.

A plain wall, made of bricks and plaster, becomes a witness to light, just as the human body, made of flesh and blood, bears witness to the soul. And that’s no small thing. Reaching that other space—moving toward the light—is a fundamental challenge for every painter, just as it is for every lover. But painting has always been done on one thing (the canvas) that hides another (the wall). The bodies of lovers, on the other hand, never hide—even when they cover one another.

Painters might say, “But I’m painting infinite space. Why does it matter if I take away some real space?” What kind of logic is that? It’s false! The infinite doesn’t tolerate negations or falsehoods. Mark Rothko, one of the greats, understood this. He was already working toward transparency, though his approach was metaphysical. He pushed color to its limits—you could feel it, sense the life vibrating beneath the canvas. The light in his work led your gaze from the center to the edges, drawing you beyond the painting itself, as if inviting you to circumvent it. That was immense. The closer you got to the edge, the clearer things became. But when you approached the painting and touched it, you realized the light was fake—made with paint. It was beautiful, yes, but it was an enormous lie. It was a color pretending to be light, not light becoming color. That’s a terrible truth to face.

Lucio Fontana, another master, also found the canvas bothersome. Like Rothko, he knew you had to go beyond the surface, beyond the canvas, toward the light. So, what did Fontana do? He said, “Canvas, I won’t paint you—I’ll cut you.” Brilliant! A powerful gesture, but one that didn’t solve the problem. The cut was theatrical, provocative, but it wasn’t entirely painting. It implied an act of beginning, a command to “go!” But I’ve come to understand that painting exists a little before and a little beyond the act of painting itself.

That said, I must confess something: there’s no intelligence in transparency. There’s no metaphysics, no grand reasoning or intention. Transparency is just a matter of necessity.

It was out of necessity that I pulled a thread from the canvas.

Out of necessity, light entered the painting through that opening.

The light reached the wall behind it.

It illuminated the wall.

And finally, by that same necessity, the light returned.

That’s all there is to it.

But when the light came back to the canvas, back into the painting, it had already done everything. It carried with it color, matter, emotion, movement, physics, metaphysics, mathematics, history, geography—everything in human space and time, and with it, the truth of God. That’s how transparency works. That’s how light becomes a message to humanity.

This is the path I’ve followed. So, can transparency truly become a new word for painting? If so, then let’s get to it—because one day, we might create paintings without bodies, fully transparent, made of nothing but light and color, without a canvas to hold them or a lie to justify them. Imagine a wall entirely transparent, made only of light and color, alive and changing with your emotions. A wall that protects you without isolating you. Imagine that, and you’re already in paradise.

What is the sky made of? Nothing.

What color is the sky? None.

The sky is empty and transparent.

And yet, its blue holds up the clouds.

Io? Appartengo alla luce

Sono nato il 25 aprile del ‘29. Anzi, per la precisione, sono venuto alla luce. E dal momento che alla luce ci sono venuto, non l’ho potuta più lasciare. Io appartengo alla luce. L’ho cercata dentro i quadri, nella pittura, ma si è trattato di un posto come un altro. La luce la inseguono i pittori come gli amanti: tutti gli altri la inseguono lo stesso, ma in altri modi. Qualcuno la trova addirittura, consumando la carne del suo stesso corpo ma quella cosa lì si chiama santità. Personalmente mi ha interessato la luce quella vera, fisica. Quella cosa chiara che permette di vedere -e noi impariamo a vedere ogni volta che apriamo gli occhi- Quella cosa bella, bellissima, che entra nei quadri e che ne tira fuori il colore. Che si muove, che cambia, ma è sempre solo lei. Che gioca con le ombre e con la materia. Quella cosa che ti fa crescere e che ti emoziona. Nella pittura, come nella vita è questo che importa veramente: l’emozione. L’emozione e la luce. Anzi, l’emozione è la luce. E’ per questo fatto che i miei quadri sono, in fondo, solo un pretesto. Il quadro non deve essere fine a sé stesso. Meglio ancora se non è affatto finito. Il quadro è ipotesi, possibilità. Non è una cosa ferma, non è né un’immagine e né un concetto. E’ movimento. Il quadro è quando lo spazio si mette a fare l’amore col tempo.

E quando si fa all’amore è difficile a restarsene fermi. Ma allora, mi direte, i quadri non ce l’hanno un significato? Certo! Ma la luce è in sé il significato, è un messaggio. E’ verità. E la verità poi, è mobile proprio come la luce. Leonardo cinque secoli fa diceva “Per raggiungere l’essenzialità delle cose bisogna togliere e non aggiungere!”. E noi per gli stessi cinque secoli abbiamo continuato con ‘sta stupidaggine autentica, di aggiungere pittura alla pittura, gesti ai gesti, parole alle parole. Ma che possibilità diamo al quadro se noi lo affoghiamo di forme, di concetti, di immagini, di significati? Dal momento che io do un significato, un nome, una ragione ad una cosa, io questa cosa la condanno alla limitazione. A quella che è la mia stessa limitazione. Vi faccio un esempio: Se io vedo una bella donna, la verità è che quella donna è bella. Basta. Mi emoziona, questa donna, mi manda in Paradiso. Detto questo, che me ne frega a me come si chiama, chi è, chi non è. Se questa donna è figurativa oppure concettuale. Tutte queste considerazioni, quando ho visto una verità piena e rotonda come ’sta emozione di femmina bella, diventano inutili. Io ho già guardato oltre i vestiti, oltre lo stesso suo corpo e ho veduto quella luce che questa donna si porta appresso. E ogni donna, se ne porta sempre appresso una. Che cos’è la trasparenza allora, se non il tentativo di eliminare ogni corpo opaco che si metta in mezzo tra i nostri occhi e la luce? Per secoli lo spazio dietro al quadro è stato uno spazio morto. Era necessario far vivere quello spazio, perché è là che la verità aspetta di essere scoperta, ancora ed ancora. La trasparenza è questo proprio, andare all’altro spazio, quello spazio che raramente nella vita si raggiunge: è la verità quello spazio, è il paradiso, è un muro. Un muro qualsiasi, che, però, grazie alla trasparenza diventa un luogo, abitabile dall’uomo e dalla vita. Quel muro di materia, fatto di mattoni ed intonaco, testimonia per la prima volta, la luce. Come da sempre, il corpo, di carne e sangue, testimonia dell' anima. E non è mica poco. Raggiungere L’Altro Spazio, andare alla Luce, è un problema fondamentale per tutti i pittori, come per gli amanti. Ma la pittura si è sempre fatta su un cosa (il quadro) che ne nascondeva un'altra (il muro). I corpi degli amanti invece, quelli, non si nascondono mai, nemmeno quando si coprono l’un l’altro. I pittori ti dicono: “Ma io ti dipingo lo spazio infinito, che t’importa se ti tolgo un poco di spazio reale”. E che discorso è? E’ Falsità! L’Infinito non ammette negazioni, non ammette falsità. Mark Rothko, uno dei grandissimi, lo aveva capito questo. Già faceva trasparenza, ma la sua era una cosa metafisica. Lui tirava al massimo il colore, te lo faceva sentire, ti faceva avvertire la tela sotto che vibrava, intuivi che c’era una vita dietro. E la luce ti spostava lo sguardo dal centro verso il margine, fuori dal quadro, come per aggirarlo. La luce ti imponeva di muoverti verso la sua fonte, e questa, è una cosa immensa. E più andavi al margine più la cosa si faceva nitida, chiara. Poi, però, ti avvicinavi al quadro, lo andavi a toccare e ti accorgevi che quella luce era finta, era fatta con la pittura. Era bella quella luce là, caspita, ma era una menzogna tremenda. Era un colore che ti dava l’idea di essere una luce, ma non certo la luce che diventava lei stessa, il colore. Un fatto tremendo questo, terribile. Pure a Lucio Fontana, un altro grandissimo, dava fastidio il quadro. Era cosciente, come Rothko, che bisognava andare oltre la superficie della tela, oltre il quadro, verso la luce. Che disse allora, Fontana: “Quadro, io non ti voglio dipingere, io ti taglio”. Una cosa intelligentissima questa, una protesta, che però ancora una volta non risolveva il problema. Il Taglio era un fatto di teatro, era una provocazione lucidissima, radicale, ma non apparteneva interamente alla Pittura. Presupponeva una gestualità, un atto d’inizio: un Via! Ed io, invece, ho dovuto capire che la pittura esiste sempre un poco prima ed un poco oltre dell’atto di dipingere. Detto tutto questo, devo confessare una cosa. Non c’è nessuna intelligenza nella trasparenza. Non c’è metafisica, alcuna difficoltà, ragione o volontà. La trasparenza è solamente un fatto di Necessità.

E’ stata una necessità per me tirare un filo dalla tela.

Per necessità da quel varco, la luce è entrata nel quadro.

E la luce è arrivata fino al muro.

E l’ha illuminato, il muro.

Ed alla fine, sempre per la stessa necessità iniziale, la luce è tornata indietro.

Questo è quanto.

Ma quando è tornata indietro sulla tela, nel quadro, Quella lì, la luce, aveva già fatto tutto. Si era portata appresso il colore, la materia, l’emozione, il movimento, la fisica, la metafisica, la matematica, la storia, la geografia. Tutto lo spazio del mondo e tutto il tempo dell’uomo e, con queste cose, tutta la verità di Dio. E’ così che funziona la trasparenza: è così che la luce diventa messaggio all’umanità. E’ questa la strada che ho seguito. Può essere, quindi la trasparenza, davvero una parola nuova per la pittura? Se è vero questo, allora diamoci sotto, diamoci da fare, perché un giorno arriveremo a concepire quadri senza corpo, totalmente trasparenti, fatti solo di luce e di colore, senza tela che li sostenga. Senza menzogna che li giustifichi. Immagina, una parete completamente trasparente, fatta solo di luce e di colore, che viva, che cambi appresso alle emozioni tue. Che ti protegga senza per questo isolarti. Immagina: e sei in paradiso.

Di cos’è fatto il Cielo? Di niente!<br>

Di che colore è il Cielo? Nessuno!<br>

Il Cielo è Vuoto e Trasparente.<br>

Eppure d’Azzurro sostiene le Nuvole.<br>

I was born on April 25, 1929—or, to be precise, I came into the light. And from the moment I did, I could never let it go. I belong to the light. I sought it in my paintings, through painting, but that was just one place among many. Painters chase light like lovers; everyone else does too, but in their own ways. Some even find it by consuming the very flesh of their bodies, though that is called sainthood. Personally, I was interested in real light, physical light. That clear thing that allows us to see—and we learn to see every time we open our eyes. That beautiful, radiant thing that enters paintings and pulls color out of them. That moves, that changes, yet remains the same. That plays with shadows and matter. That thing that makes you grow and that moves you deeply. In painting, as in life, that’s what really matters: emotion. Emotion and light. Actually, emotion is light. For this reason, my paintings are, in the end, just a pretext. A painting shouldn’t be an end in itself. Better if it isn’t finished at all. A painting is a hypothesis, a possibility. It isn’t something fixed, nor is it an image or a concept. It’s movement. A painting is when space begins to make love with time.

And when it comes to making love, staying still is nearly impossible. So, you might ask, do paintings have no meaning? Of course, they do! But light itself is meaning—it’s a message. It’s truth. And truth, like light, is always in motion. Five centuries ago, Leonardo said, “To get to the essence of things, you must remove, not add!” And yet, for the same five centuries, we’ve stubbornly insisted on doing the opposite—layering paint upon paint, gestures upon gestures, words upon words. But what chance do we give a painting if we smother it with forms, concepts, images, and meanings?

The moment we assign a meaning, a name, or a reason to something, we limit it—we trap it within the bounds of our own limitations. Let me give you an example. If I see a beautiful woman, the truth is simple: she is beautiful. That’s it. She stirs me, she lifts me to paradise. Beyond that, what do I care about her name, her identity, or whether she’s figurative or conceptual? When confronted with a truth as full and radiant as the beauty of a woman, all those questions fade away. I’ve already looked beyond her clothes, beyond even her body, and I’ve seen the light she carries. Every woman carries a light within her.

So, what is transparency, if not an effort to remove every opaque barrier that stands between our eyes and the light? For centuries, the space behind a painting was a dead space. That space needed to come alive because that’s where truth waits to be discovered, again and again. Transparency is precisely this: reaching for another space—the space where truth resides, where paradise lies, where even a simple wall becomes something extraordinary.

A plain wall, made of bricks and plaster, becomes a witness to light, just as the human body, made of flesh and blood, bears witness to the soul. And that’s no small thing. Reaching that other space—moving toward the light—is a fundamental challenge for every painter, just as it is for every lover. But painting has always been done on one thing (the canvas) that hides another (the wall). The bodies of lovers, on the other hand, never hide—even when they cover one another.

Painters might say, “But I’m painting infinite space. Why does it matter if I take away some real space?” What kind of logic is that? It’s false! The infinite doesn’t tolerate negations or falsehoods. Mark Rothko, one of the greats, understood this. He was already working toward transparency, though his approach was metaphysical. He pushed color to its limits—you could feel it, sense the life vibrating beneath the canvas. The light in his work led your gaze from the center to the edges, drawing you beyond the painting itself, as if inviting you to circumvent it. That was immense. The closer you got to the edge, the clearer things became. But when you approached the painting and touched it, you realized the light was fake—made with paint. It was beautiful, yes, but it was an enormous lie. It was a color pretending to be light, not light becoming color. That’s a terrible truth to face.

Lucio Fontana, another master, also found the canvas bothersome. Like Rothko, he knew you had to go beyond the surface, beyond the canvas, toward the light. So, what did Fontana do? He said, “Canvas, I won’t paint you—I’ll cut you.” Brilliant! A powerful gesture, but one that didn’t solve the problem. The cut was theatrical, provocative, but it wasn’t entirely painting. It implied an act of beginning, a command to “go!” But I’ve come to understand that painting exists a little before and a little beyond the act of painting itself.

That said, I must confess something: there’s no intelligence in transparency. There’s no metaphysics, no grand reasoning or intention. Transparency is just a matter of necessity.

It was out of necessity that I pulled a thread from the canvas.

Out of necessity, light entered the painting through that opening.

The light reached the wall behind it.

It illuminated the wall.

And finally, by that same necessity, the light returned.

That’s all there is to it.

But when the light came back to the canvas, back into the painting, it had already done everything. It carried with it color, matter, emotion, movement, physics, metaphysics, mathematics, history, geography—everything in human space and time, and with it, the truth of God. That’s how transparency works. That’s how light becomes a message to humanity.

This is the path I’ve followed. So, can transparency truly become a new word for painting? If so, then let’s get to it—because one day, we might create paintings without bodies, fully transparent, made of nothing but light and color, without a canvas to hold them or a lie to justify them. Imagine a wall entirely transparent, made only of light and color, alive and changing with your emotions. A wall that protects you without isolating you. Imagine that, and you’re already in paradise.

What is the sky made of? Nothing.

What color is the sky? None.

The sky is empty and transparent.

And yet, its blue holds up the clouds.

Me?

I Belong to the Light

Io? Appartengo alla luce

Sono nato il 25 aprile del ‘29. Anzi, per la precisione, sono venuto alla luce. E dal momento che alla luce ci sono venuto, non l’ho potuta più lasciare. Io appartengo alla luce. L’ho cercata dentro i quadri, nella pittura, ma si è trattato di un posto come un altro. La luce la inseguono i pittori come gli amanti: tutti gli altri la inseguono lo stesso, ma in altri modi. Qualcuno la trova addirittura, consumando la carne del suo stesso corpo ma quella cosa lì si chiama santità. Personalmente mi ha interessato la luce quella vera, fisica. Quella cosa chiara che permette di vedere -e noi impariamo a vedere ogni volta che apriamo gli occhi- Quella cosa bella, bellissima, che entra nei quadri e che ne tira fuori il colore. Che si muove, che cambia, ma è sempre solo lei. Che gioca con le ombre e con la materia. Quella cosa che ti fa crescere e che ti emoziona. Nella pittura, come nella vita è questo che importa veramente: l’emozione. L’emozione e la luce. Anzi, l’emozione è la luce. E’ per questo fatto che i miei quadri sono, in fondo, solo un pretesto. Il quadro non deve essere fine a sé stesso. Meglio ancora se non è affatto finito. Il quadro è ipotesi, possibilità. Non è una cosa ferma, non è né un’immagine e né un concetto. E’ movimento. Il quadro è quando lo spazio si mette a fare l’amore col tempo.

E quando si fa all’amore è difficile a restarsene fermi. Ma allora, mi direte, i quadri non ce l’hanno un significato? Certo! Ma la luce è in sé il significato, è un messaggio. E’ verità. E la verità poi, è mobile proprio come la luce. Leonardo cinque secoli fa diceva “Per raggiungere l’essenzialità delle cose bisogna togliere e non aggiungere!”. E noi per gli stessi cinque secoli abbiamo continuato con ‘sta stupidaggine autentica, di aggiungere pittura alla pittura, gesti ai gesti, parole alle parole. Ma che possibilità diamo al quadro se noi lo affoghiamo di forme, di concetti, di immagini, di significati? Dal momento che io do un significato, un nome, una ragione ad una cosa, io questa cosa la condanno alla limitazione. A quella che è la mia stessa limitazione. Vi faccio un esempio: Se io vedo una bella donna, la verità è che quella donna è bella. Basta. Mi emoziona, questa donna, mi manda in Paradiso. Detto questo, che me ne frega a me come si chiama, chi è, chi non è. Se questa donna è figurativa oppure concettuale. Tutte queste considerazioni, quando ho visto una verità piena e rotonda come ’sta emozione di femmina bella, diventano inutili. Io ho già guardato oltre i vestiti, oltre lo stesso suo corpo e ho veduto quella luce che questa donna si porta appresso. E ogni donna, se ne porta sempre appresso una. Che cos’è la trasparenza allora, se non il tentativo di eliminare ogni corpo opaco che si metta in mezzo tra i nostri occhi e la luce? Per secoli lo spazio dietro al quadro è stato uno spazio morto. Era necessario far vivere quello spazio, perché è là che la verità aspetta di essere scoperta, ancora ed ancora. La trasparenza è questo proprio, andare all’altro spazio, quello spazio che raramente nella vita si raggiunge: è la verità quello spazio, è il paradiso, è un muro. Un muro qualsiasi, che, però, grazie alla trasparenza diventa un luogo, abitabile dall’uomo e dalla vita. Quel muro di materia, fatto di mattoni ed intonaco, testimonia per la prima volta, la luce. Come da sempre, il corpo, di carne e sangue, testimonia dell' anima. E non è mica poco. Raggiungere L’Altro Spazio, andare alla Luce, è un problema fondamentale per tutti i pittori, come per gli amanti. Ma la pittura si è sempre fatta su un cosa (il quadro) che ne nascondeva un'altra (il muro). I corpi degli amanti invece, quelli, non si nascondono mai, nemmeno quando si coprono l’un l’altro. I pittori ti dicono: “Ma io ti dipingo lo spazio infinito, che t’importa se ti tolgo un poco di spazio reale”. E che discorso è? E’ Falsità! L’Infinito non ammette negazioni, non ammette falsità. Mark Rothko, uno dei grandissimi, lo aveva capito questo. Già faceva trasparenza, ma la sua era una cosa metafisica. Lui tirava al massimo il colore, te lo faceva sentire, ti faceva avvertire la tela sotto che vibrava, intuivi che c’era una vita dietro. E la luce ti spostava lo sguardo dal centro verso il margine, fuori dal quadro, come per aggirarlo. La luce ti imponeva di muoverti verso la sua fonte, e questa, è una cosa immensa. E più andavi al margine più la cosa si faceva nitida, chiara. Poi, però, ti avvicinavi al quadro, lo andavi a toccare e ti accorgevi che quella luce era finta, era fatta con la pittura. Era bella quella luce là, caspita, ma era una menzogna tremenda. Era un colore che ti dava l’idea di essere una luce, ma non certo la luce che diventava lei stessa, il colore. Un fatto tremendo questo, terribile. Pure a Lucio Fontana, un altro grandissimo, dava fastidio il quadro. Era cosciente, come Rothko, che bisognava andare oltre la superficie della tela, oltre il quadro, verso la luce. Che disse allora, Fontana: “Quadro, io non ti voglio dipingere, io ti taglio”. Una cosa intelligentissima questa, una protesta, che però ancora una volta non risolveva il problema. Il Taglio era un fatto di teatro, era una provocazione lucidissima, radicale, ma non apparteneva interamente alla Pittura. Presupponeva una gestualità, un atto d’inizio: un Via! Ed io, invece, ho dovuto capire che la pittura esiste sempre un poco prima ed un poco oltre dell’atto di dipingere. Detto tutto questo, devo confessare una cosa. Non c’è nessuna intelligenza nella trasparenza. Non c’è metafisica, alcuna difficoltà, ragione o volontà. La trasparenza è solamente un fatto di Necessità.

E’ stata una necessità per me tirare un filo dalla tela.

Per necessità da quel varco, la luce è entrata nel quadro.

E la luce è arrivata fino al muro.

E l’ha illuminato, il muro.

Ed alla fine, sempre per la stessa necessità iniziale, la luce è tornata indietro.

Questo è quanto.

Ma quando è tornata indietro sulla tela, nel quadro, Quella lì, la luce, aveva già fatto tutto. Si era portata appresso il colore, la materia, l’emozione, il movimento, la fisica, la metafisica, la matematica, la storia, la geografia. Tutto lo spazio del mondo e tutto il tempo dell’uomo e, con queste cose, tutta la verità di Dio. E’ così che funziona la trasparenza: è così che la luce diventa messaggio all’umanità. E’ questa la strada che ho seguito. Può essere, quindi la trasparenza, davvero una parola nuova per la pittura? Se è vero questo, allora diamoci sotto, diamoci da fare, perché un giorno arriveremo a concepire quadri senza corpo, totalmente trasparenti, fatti solo di luce e di colore, senza tela che li sostenga. Senza menzogna che li giustifichi. Immagina, una parete completamente trasparente, fatta solo di luce e di colore, che viva, che cambi appresso alle emozioni tue. Che ti protegga senza per questo isolarti. Immagina: e sei in paradiso.

Di cos’è fatto il Cielo? Di niente!<br>

Di che colore è il Cielo? Nessuno!<br>

Il Cielo è Vuoto e Trasparente.<br>

Eppure d’Azzurro sostiene le Nuvole.<br>

I was born on April 25, 1929—or, to be precise, I came into the light. And from the moment I did, I could never let it go. I belong to the light. I sought it in my paintings, through painting, but that was just one place among many. Painters chase light like lovers; everyone else does too, but in their own ways. Some even find it by consuming the very flesh of their bodies, though that is called sainthood. Personally, I was interested in real light, physical light. That clear thing that allows us to see—and we learn to see every time we open our eyes. That beautiful, radiant thing that enters paintings and pulls color out of them. That moves, that changes, yet remains the same. That plays with shadows and matter. That thing that makes you grow and that moves you deeply. In painting, as in life, that’s what really matters: emotion. Emotion and light. Actually, emotion is light. For this reason, my paintings are, in the end, just a pretext. A painting shouldn’t be an end in itself. Better if it isn’t finished at all. A painting is a hypothesis, a possibility. It isn’t something fixed, nor is it an image or a concept. It’s movement. A painting is when space begins to make love with time.

And when it comes to making love, staying still is nearly impossible. So, you might ask, do paintings have no meaning? Of course, they do! But light itself is meaning—it’s a message. It’s truth. And truth, like light, is always in motion. Five centuries ago, Leonardo said, “To get to the essence of things, you must remove, not add!” And yet, for the same five centuries, we’ve stubbornly insisted on doing the opposite—layering paint upon paint, gestures upon gestures, words upon words. But what chance do we give a painting if we smother it with forms, concepts, images, and meanings?

The moment we assign a meaning, a name, or a reason to something, we limit it—we trap it within the bounds of our own limitations. Let me give you an example. If I see a beautiful woman, the truth is simple: she is beautiful. That’s it. She stirs me, she lifts me to paradise. Beyond that, what do I care about her name, her identity, or whether she’s figurative or conceptual? When confronted with a truth as full and radiant as the beauty of a woman, all those questions fade away. I’ve already looked beyond her clothes, beyond even her body, and I’ve seen the light she carries. Every woman carries a light within her.

So, what is transparency, if not an effort to remove every opaque barrier that stands between our eyes and the light? For centuries, the space behind a painting was a dead space. That space needed to come alive because that’s where truth waits to be discovered, again and again. Transparency is precisely this: reaching for another space—the space where truth resides, where paradise lies, where even a simple wall becomes something extraordinary.

A plain wall, made of bricks and plaster, becomes a witness to light, just as the human body, made of flesh and blood, bears witness to the soul. And that’s no small thing. Reaching that other space—moving toward the light—is a fundamental challenge for every painter, just as it is for every lover. But painting has always been done on one thing (the canvas) that hides another (the wall). The bodies of lovers, on the other hand, never hide—even when they cover one another.

Painters might say, “But I’m painting infinite space. Why does it matter if I take away some real space?” What kind of logic is that? It’s false! The infinite doesn’t tolerate negations or falsehoods. Mark Rothko, one of the greats, understood this. He was already working toward transparency, though his approach was metaphysical. He pushed color to its limits—you could feel it, sense the life vibrating beneath the canvas. The light in his work led your gaze from the center to the edges, drawing you beyond the painting itself, as if inviting you to circumvent it. That was immense. The closer you got to the edge, the clearer things became. But when you approached the painting and touched it, you realized the light was fake—made with paint. It was beautiful, yes, but it was an enormous lie. It was a color pretending to be light, not light becoming color. That’s a terrible truth to face.

Lucio Fontana, another master, also found the canvas bothersome. Like Rothko, he knew you had to go beyond the surface, beyond the canvas, toward the light. So, what did Fontana do? He said, “Canvas, I won’t paint you—I’ll cut you.” Brilliant! A powerful gesture, but one that didn’t solve the problem. The cut was theatrical, provocative, but it wasn’t entirely painting. It implied an act of beginning, a command to “go!” But I’ve come to understand that painting exists a little before and a little beyond the act of painting itself.

That said, I must confess something: there’s no intelligence in transparency. There’s no metaphysics, no grand reasoning or intention. Transparency is just a matter of necessity.

It was out of necessity that I pulled a thread from the canvas.

Out of necessity, light entered the painting through that opening.

The light reached the wall behind it.

It illuminated the wall.

And finally, by that same necessity, the light returned.

That’s all there is to it.

But when the light came back to the canvas, back into the painting, it had already done everything. It carried with it color, matter, emotion, movement, physics, metaphysics, mathematics, history, geography—everything in human space and time, and with it, the truth of God. That’s how transparency works. That’s how light becomes a message to humanity.

This is the path I’ve followed. So, can transparency truly become a new word for painting? If so, then let’s get to it—because one day, we might create paintings without bodies, fully transparent, made of nothing but light and color, without a canvas to hold them or a lie to justify them. Imagine a wall entirely transparent, made only of light and color, alive and changing with your emotions. A wall that protects you without isolating you. Imagine that, and you’re already in paradise.

What is the sky made of? Nothing.

What color is the sky? None.

The sky is empty and transparent.

And yet, its blue holds up the clouds.

Me?

I Belong to the Light

- Via Salvatore Emblema, 37,

Terzigno, IT 80040 - + 39 081 8274081

- museo@salvatoreemblema.it

archivio@salvatoreemblema.it

didattica@salvatoreemblema.it

Writings on this website are literary reworkings on interviews, memoirs, and suggestions made by the artist’s heirs. They are also drown from audiovisual materials, documents, recordings kept in the archives of Museo Emblema.

- da lun- ven 9:00 -13:00

sab-dom su prenotazione

Address List

- Via Salvatore Emblema, 37,

Terzigno, IT 80040 - + 39 081 8274081

- museo@salvatoreemblema.it

archivio@salvatoreemblema.it

didattica@salvatoreemblema.it

HOURS

- da lun- ven 9:00 -13:00

sab-dom su prenotazione

PARTNER

Writings on this website are literary reworkings on interviews, memoirs, and suggestions made by the artist’s heirs. They are also drown from audiovisual materials, documents, recordings kept in the archives of Museo Emblema.